Description

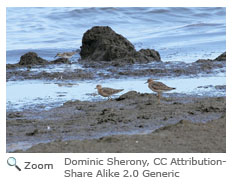

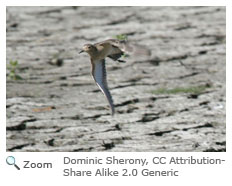

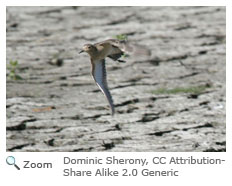

A medium-sized shorebird, the Buff-breasted Sandpiper is light brown all over with small black spots on the head, back and wings. The undersides of the wings are white. It has a short, pointed black bill and long yellow legs. A medium-sized shorebird, the Buff-breasted Sandpiper is light brown all over with small black spots on the head, back and wings. The undersides of the wings are white. It has a short, pointed black bill and long yellow legs.

Range

The Buff-breasted Sandpiper makes an incredible migration. It spends the winter in the South American countries of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. Males and females start to leave South America in February and begin the flight north as early as mid-June. The Sandpiper arrives in the arctic region of Canada and Alaska to spend the breeding season.

Habitat

The Buff-breasted Sandpiper breeds in dry, grassy tundra. During migration, the Sandpiper is found in dry, short grassland, pasture and plowed fields. It spends the winter in flat, grassy prairie. Pampas grass is a common species of grass in the region. The Buff-breasted Sandpiper breeds in dry, grassy tundra. During migration, the Sandpiper is found in dry, short grassland, pasture and plowed fields. It spends the winter in flat, grassy prairie. Pampas grass is a common species of grass in the region. |

|

Diet

An omnivore, the Buff-breasted Sandpiper is known to eat flies, midges, crane flies, beetles, spiders and seeds from aquatic plants. To hunt, the Sandpiper stands perfectly still and scans the ground until it can snatch an insect with its sharp bill. An omnivore, the Buff-breasted Sandpiper is known to eat flies, midges, crane flies, beetles, spiders and seeds from aquatic plants. To hunt, the Sandpiper stands perfectly still and scans the ground until it can snatch an insect with its sharp bill.

Life Cycle

During breeding season, males gather in a group called a lek, where they perform breeding displays to females. After mating, male and female Sandpipers do not form pairs. The female builds a nest and incubates the eggs by herself. During breeding season, males gather in a group called a lek, where they perform breeding displays to females. After mating, male and female Sandpipers do not form pairs. The female builds a nest and incubates the eggs by herself.

The female makes a depression in thick moss and lines it with lichens, leaves and grass to form a nest. She lays four spotted eggs which are incubated for about 24 days. Upon hatching, chicks are well developed; they can run, feed themselves and hide from predators.

Behavior

The population of Buff-breasted Sandpipers declined from millions to near extinction by the 1920s. Numbers have seemed to increase but may be in decline again. The population of Buff-breasted Sandpipers declined from millions to near extinction by the 1920s. Numbers have seemed to increase but may be in decline again. |